How to write about grief without drowning

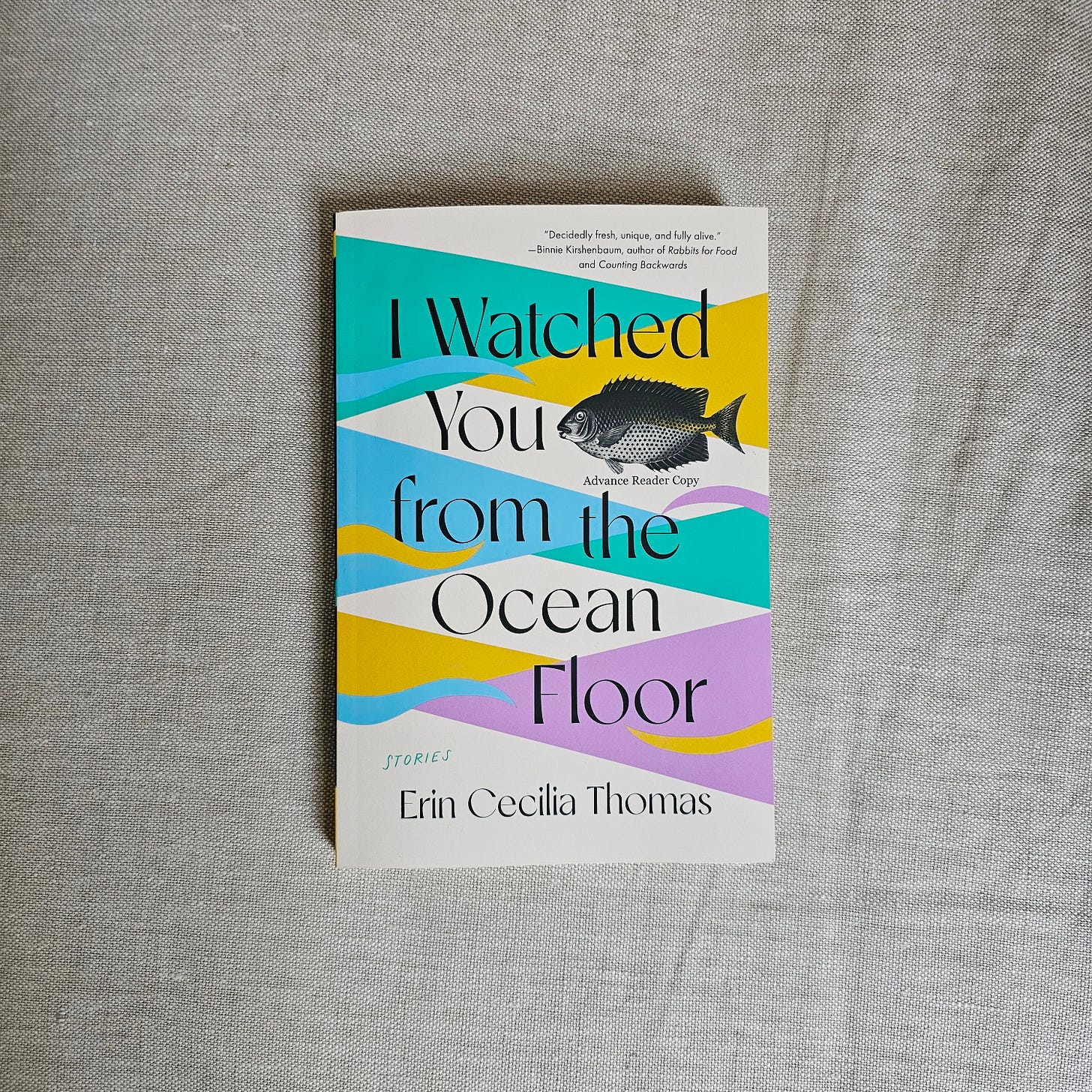

Q&A with Erin Cecilia Thomas, author of I WATCHED YOU FROM THE OCEAN FLOOR.

“The icy silence that fell in Chelsea and in their house was a cold that Elena recognized. It was the quiet of loss, the sound of something missing.”

—Erin Cecilia Thomas, from “Washington Avenue”

There’s a lot about the grieving process we don’t discus publicly. Sometimes our sadness feels too small. Sometimes it’s quirky. Sometimes we do things we never expected to do, or need something we never expected to need.

Loss is nuanced and personal. It doesn’t fit into a box or follow a linear timeline. It can be messy, confusing, and inconvenient. It can permeate everything we do moving forward. It can recede, then circle back around again during a big life transition, or while rolling the garbage can to the curb.

It can feel like slowly dipping underwater, then coming up for air, then submerging again.

A thread that resounded throughout Erin Cecilia Thomas’s debut short story collection, I WATCHED YOU FROM THE OCEAN FLOOR, is that grief—in all its forms—is at its very core, an experience involving witnessing and being witnessed.

As one character says, “That’s the trouble today, isn’t it? Too easy to just clear things away, too easy to just hit ‘Delete.’”

To look closer, to not push it all under the rug, and to discuss writing through hard things (which so many of us do!), I’m delighted to share this Q&A with Erin. If this conversation resonates, I hope you’ll pre-order her book, out July 1 from Modern Artist Press.

Erin Cecilia Thomas is from Buffalo, New York. She graduated from Berklee College of Music and went on to receive her MFA from Lesley University. Her work has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Arts & Letters, and Redivider Journal, among many others. In 2021, she was the recipient of the Beacon Street Prize in Fiction. She has lived in Boston, Brooklyn, and New Jersey, and she currently resides in Nashville with her husband and their dog. I Watched You From The Ocean Floor is her first book.

Congratulations on this collection! It’s beautiful. How are you holding up in the weeks leading up to publication?

Thank you! I’m excited. The book itself has been a year in the making, and some of the stories were first drafted as many as seven years ago. I’m ready for it to be out in the world.

Some of these stories were published in journals. Did you start with separate stories and then realize you had a through line, or were you always writing towards a book-length collection?

The stories were written completely separately, and I never even considered that they would make a cohesive collection. They were written between 2018 and 2024, in different stages of my writing life, and I actually thought that they were all too different to really work together. Kathryn from Modern Artist Press was the one to see a common thread and voice through the collection, despite how different the stories might seem.

I noticed a lot of grief and. Grief and hope. Grief and beauty. In the story about the early days of the pandemic, music is one of the balms. Can you talk more about the importance of pairing really hard stuff with moments of humanity?

There’s a line in the pandemic story, “Washington Avenue,” where a young woman’s father tells her, “It’s hard to survive in this world sometimes. But you always have to leave space for beauty.” In that story, the beauty is music. In another story, the beauty is found in a girl’s love for her pet chicken. The most significant thread of beauty through the collection is how we manage to overcome the hard stuff together, or at least we’re able to cope a little more easily.

I’m guilty of letting myself get overwhelmed with the onslaught of bad news in the world, and grief is something I’ve always had to pull myself out of. But I’m getting better at letting small moments of happiness pull me out of it; my dog rolling in the warm grass, a crusty piece of homemade bread, an encouraging text from a friend. It’s important to let yourself feel the hard stuff, but also important to not let yourself drown, and sometimes the only way you can manage that is with the tiniest spark of warmth. That’s what I wanted for my characters in this collection.

I’m guilty of letting myself get overwhelmed with the onslaught of bad news in the world, and grief is something I’ve always had to pull myself out of. But I’m getting better at letting small moments of happiness pull me out of it; my dog rolling in the warm grass, a crusty piece of homemade bread, an encouraging text from a friend.

One of the stories I enjoyed most was “So You May Sleep Again,” where a young widow stitches her late husband’s face on a pillow, then turns it into a business. At one point, the daughter of a client is horrified to find her father’s face on the bed, and insists her mother return it. The shame of that really struck me. There’s less of a question here and more a recognition of how easy it is to shame others (and ourselves) when grief makes us feel unmoored, or presents as strange or odd to other people.

I’ve always been very in touch with the part of myself that feels grief and, in a way, embraces sadness. That’s not to say I romanticize it, but grief is universal and is something that needs to be acknowledged and felt in order to work through it. On social media especially there’s so much emphasis put on being in control and doing all the right things to keep yourself happy. It’s easy to feel like you’re failing the wellness game during periods of grief.

The daughter in the story is a psychology student, and very caught up in the “correct and acceptable” techniques for grieving. She sees her mother grieving in her own way, with this embroidered portrait of her late husband, and thinks she knows better. At the same time, the daughter hasn’t worked through her own grief, and that creates a larger rift between her and her mother. People can find comfort and healing in unexpected and strange ways, and I wanted to infuse each of these stories with some of that strangeness.

Your stories have ambiguous endings with questions left unanswered or fates of characters unknown. That's life! Did you ever feel pulled to wrap things up in a tidy way because that might be what we crave deep down, or what we think society expects?

Not at all. Like you said, that’s life! I wanted these stories to have a larger life than the 20-ish pages they occupy, and that meant letting the endings open up instead of close down. I think short stories can be made to feel small when the entire lifespan is confined to a few pages. But it can be risky too, there’s a really fine line between leaving a reader hanging in an unsatisfying way and letting the reader take the story with them afterwards, as they close the book and go about their day. I hope these are the kinds of stories that linger in a reader’s mind because the endings aren’t wrapped up neatly, and they can imagine the kind of endings that they need.

Self-doubt is something we talk a lot about in my writing community. Was there a point in the writing process where you felt like you couldn’t do it? And if so, how did you notice it, move through it, and move forward?

Self-doubt is the constant companion of every writer I know, myself included. For me, it actually rears its head most after the story is written. I get excited by an idea, work through the story to the end, and only once I start sending it out into the world, either by workshopping with others or by submitting it for publication, do I start to second guess myself.

You can never control how others are going to receive something, and some of the stories I’ve felt most confident in have gotten the most lukewarm reactions. Some of the stories in this collection were rejected more than 25 times by different publications. But how do I keep going? Just by having a strong sense of myself and my reasons for being a writer. I know I’m not going to sell millions of books, because my stories might not appeal to that wide of an audience. But as long as I can be excited about the little worlds I create, the characters and settings and all the strange little moments of sadness and beauty, I’ll keep writing.

I once spoke with a writer who wrote a very heavy book, and her saving grace was watching reality TV. There had to be something light to counterbalance the subject matter. When writing tough topics and emotional scenes, how do you care for yourself so you're able to be in the work day after day? Another way to put it: How do you write about grief without drowning?

Changing my environment after working on something particularly heavy is helpful. If I’m writing in my room, I’ll go outside to the porch or I’ll take my dog for a walk or a hike. Being outside, particularly somewhere quiet, helps me center myself. Even small things like making a hot cup of tea can help bring me out of whatever darker mindset was needed to work on a piece about grief or loss. But there’s also the satisfaction of creating something with the power to make yourself feel deeply, even if it is mournful or heavy.

If I’m writing a scene that’s supposed to be powerful and I don’t have a powerful reaction to it myself, then it’s not working. So if I come away from writing about grief, and I’m feeling that heavy sense of loss myself, at least I know the emotions in the writing are genuine. I don’t want to write anything that’s not honest or genuine, ever.

Thank you, Erin!

Until next time,

Nicole

Thank you for this Q&A. The book looks gorgeous - I’ve pre-ordered.

This resonates thank you, just reminded me of a scroll quote: I didn’t follow the path —but I kept the scalpel. Because even poets need precision. https://www.thehiddenclinic.com/p/between-mario-kart-and-morphine